Lorida O. DVM, PhD Candidate, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki | Kotanidou E. DVM, MSc student, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Gkiouzelis Ch. Undergraduate student of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Katsakouli P. N. Undergraduate student of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Papadimitriou S. DVM, DDS, PhD, Professor, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

MeSH keywords: lingual displacement, canine, orthodontics, dog

Abstract

Introduction

Lingual displacement of the permanent mandibular canines is a common orthodontic disorder in dogs. Causes include dental and/or skeletal abnormalities, while congenital and acquired factors are also involved. The most common cause is retention of deciduous canines. This condition can lead to dysphagia, hypersalivation, and trauma to the gingiva of the maxilla and the mucosa of the hard palate, even the bone itself, leading to the formation of an oronasal fistula. Treatment can be surgical or orthodontic. The most prominent type of surgery is the extraction of the mandibular canine. However, it is a painful and technically demanding operation, which deprives the dentition of a tooth of great functionality.

Material and methods

In this study, the implemented orthodontic tech- niques and follow-up of 15 cases of dogs that were referred to the clinic, for lingual displacement of the mandibular canines, are described. The techniques used were: a) the crown extension of the mandibular canines and b) the inclined plane of acrylic resin that was placed on the maxilla. In addition to the first method, depending on the specificity of each case, an elastic orthodontic chain was used in combination with orthodontic brackets. In all dogs with retention of deciduous canines, extraction was performed first.

Results

The first method was used in 13 cases with a 100% success rate, a percentage that agrees with published international literature, offering reduced complications to the dog. Similar success rate was documented with the additional technique which was used in 2 of the 13 dogs. The second method was used in 2 dogs with 50% success rate, since the re-implantation of the device in one of the cases, led to damage and revelation of the pulp.

Discussion

In conclusion, the choice of the appropriate therapeutic method must be individualized, while the patient’s cooperation and the owner’s understanding of the particularities of orthodontic treatment are vital for the outcome of the case.

Introduction

Lingual displacement of mandibular canines is a common orthodontic anomaly in dogs. Causes of this kind of malocclusion can be a dental or skeletal abnormality or a combination of them. It appears bilaterally or unilaterally, while the abnormal position of the canine usually occurs in the permanent dentition, but can also appear in the deciduous one. Hereditary as well as acquired factors are involved (Oakes & Beard 1992, Furman & Niemiec 2013, Kim et al. 2015, Storli et al. 2018, Peruga et al. 2022). It can occur in all breeds of dogs, but most often occurs in the dolichocephalic breeds Vizsla and Weimaraner, as well as in the small and dwarf breeds (Oakes & Beard 1992, Caiafa 2019).

In normal occlusion, the mandibular canines are located in the interdental space, between the third maxillary incisor and the maxillary canine, without contacting the soft tissues or teeth. When one or both canines are displaced lingually, then injury can occur to the maxillary gingiva, hard palate mucosa, adjacent teeth, and even the incisor and maxillary bone. This condition can lead to an oronasal fistula. The injury causes inflammation, pain and intense discomfort to the animal, both during chewing of food and passive movements of the mouth. Furthermore, it can lead to periodontal and endodontic disease of the involved teeth, tooth fractures, impaired jaw development and chronic pain (Verhaert 1999, Bannon & Baker 2008, Legendre & Stepaniuk 2008, Kim et al. 2015, Storli et al. 2018). Many surgical and orthodontic techniques have been described to eliminate the aforementioned clinical signs.

Surgically, various treatment methods are reported, such as resection of part of the interdental gingiva between the upper canine and the third incisor, which allows access to the displaced mandibular canine to come into its normal position (Surgeon, 2005). The extraction of the canine causing the injury is a satisfactory solution, but the surgical procedure presents several technical difficulties and post-operative pain. Moreover, mandibular canines are supporting teeth for the jaw-bone, as their root makes up 80% of the cross-section of the mandible in the area. Additionally, the loss of this tooth is associated with hypersalivation, as well as tongue drop (Furman & Nieniec 2013, Legendre & Reiter 2018, Storli et al. 2018). Amputation of part of the crown of the displaced tooth and vital pulp therapy are alternative surgical techniques. However, appropriate radiographic equipment and regular rechecks are required to confirm the vitality of the tooth (Legendre 1994, Luotonen et al. 2014, Legendre & Reiter 2018).

The orthodontic operation is carried out on the permanent dentition, while the dog’s owner should also be trained. Orthodontic appliances can be either mobile or fixed. Various devices are used after assessment and planning of the tooth movement path. An inclined plane orthodontic device, fixed to the maxillary teeth, can be used, which can be constructed by the surgeon with self-curing cold polymerization acrylic resin, but also by a dental technician made of acrylic material or metal after taking impressions of the maxillary teeth and the maxilla. In addition, this category includes devices that consist of a combination of orthodontic hooks and elastic orthodontic chains. Also, a combination of the techniques mentioned can be used. Fixed appliances are firmly attached to the surface of dental enamel. Extension of the crown of the displaced canine using light-curing acrylic resin is an alternative technique that provides stable passive force to the periodontal ligament (Surgeon 2005, Furman & Nieniec 2013, Kim et al. 2015, Angel 2016, Storli et al. 2018).

The present study presents a case series of mandibular canines lingual displacement, treated with orthodontic techniques described in the introduction.

Materials and methods

Fifteen dogs were presented for clinical examination at the Clinic between September 2021 and October 2022. Cases were included in the study if breed, sex, body weight, clinical picture and condition of the oral cavity at the time of presentation were recorded. The main reason for the presentation was the retention of deciduous canines; however, following clinical examination, all animals were found to have a lingual displacement of the lower permanent canines. In addition, the surgical and orthodontic techniques used, complications, and outcomes were recorded. All dogs were re-examined regularly, and the last communication with the owner was available for at least six months after the completion of orthodontic movement of the mandibular permanent canines.

In all of the cases, a series of procedures tests were carried out in order to decide the appropriate treatment plan. Firstly, according to the owner, medical history was recorded, including details regarding the dog’s food and oral hygiene, as well as its behavior. Subsequently, a clinical and dental examination was performed with the dog awake. The stage of dentition, permanent, juvenile, or mixed and the type of occlusion of dental arches were recorded according to Gorrel’s (2004) classification, which takes into account: the symmetry of the crown, the position of the maxillary and mandibular incisors, the occlusion of the canines, the alignment of the premolars, the occlusion of the premolars/molars and the position of each tooth. Finally, a blood sample was taken for the hematological and biochemical investigation of the animal’s general health.

After examination with the animal awake, all animals underwent a thorough examination of the oral cavity under general anesthesia. After obtaining the results of the pre-anesthetic check, the animals were anesthetized, the periodontium was checked with the periodontal probe, and intraoral radiographs were taken using a no. 2 digital plate. All animals were pre-medicated with dexmedetomidine 150 μg/m (Dextomidor 0,5 mg/ml, Orion Corporation Orion Pharma, Finland), induction of anesthesia was performed with administration of propofol 1 mg/kg BW (Propofol 10 mg/ml, Fresenius Kabi AG, Germany). At the same time, maintenance was achieved with the administration of isoflurane (Iso-Vet 1000 mg /g, Piramal Enterprises Limited, Ireland) in oxygen following intubation. 2 Prior to the start of the surgical procedure, dogs undergoing extraction of residual deciduous teeth were administered a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and regional nerve block with a combination of lidocaine/adrenaline. For the extraction of the juvenile canines, the technique, during which an envelope-like flap is created was chosen. With the help of a periosteum peeler, the mucosa was detached from the periosteum. Tooth extraction was performed with a Luxator type extraction lever and the flap was sutured with 4/0 monofilament absorbable suture, with simple interrupted sutures.

Figure 1. Lingual displacement of the right mandibular canine (404) (A), Crown extension of the right mandibular canine (404) (Β).

Figure 2. Lingual displacement of the left mandibular canine (404) (A), Crown extension of the left mandibular canine (404) (Β).

Two methods were used to treat the lingual displacement of the canines:

The first was the lengthening of the mandibular canines (Figure 1, 2). The crown of the mandibular canines was extented with light-curing resin and beveled, depending on the initial position of the tooth, so that its extension would be positioned in the interdental space between the ipsilateral maxillary canine and the third incisor, during occlusion of the dental barriers. After careful debridement, polishing, and drying of the displaced tooth, an abrasive agent was placed on the crown’s surface, and then it was rinsed and dried again. This was followed by the application and light-curing of an adhesive agent and composite resin placement and light-curing in layers of 2-3 mm thickness until the final shape and length of the tooth’s extension were achieved. Lastly, using a diamond burr and polishing disks, the imperfections were corrected and the tooth was polished.

Figure 3. Lingual displacement of right upper canine (404), narrow interdental space between the upper third incisor (103) and the upper canine (103) (104) (A), auxiliary method with elastic orthodontic chain.

In addition to the previous method, an elastic orthodontic chain placement was adjunctively used (Figure 3). This technique was used in cases where the interdental space between the upper canine and the upper incisor was narrower than normal. The aim of the procedure was to move the maxillary canine back and open up space to facilitate the movement of the mandibular canine. In this technique, orthodontic brackets were placed on the canine and the ipsilateral fourth premolar after its fusion with a thin metal suture and light-curing resin to the first molar. Finally, an elastic orthodontic chain was placed on the two orthodontic brackets, exerting the desired tension for the caudal movement of the canine.

Figure 4. Lingual displacement of the two mandibular canines (304, 404) (A, B), Acrylic resin inclined plane (C), Metal inclined plane (D).

The second method used was the inclined plane method (Figure 4). In this technique, an abrading agent was initially placed on the maxillary incisors, the canine and some of the premolars, depending on the requirements of the case, the abrading agent was washed off and the teeth were dried. An adhesive light-curing agent, and ultimately a cold-curing resin, were placed on all the abraded teeth. A smooth 45°-60° inclined plane was shaped to guide the tooth into the interdental space between the lateral upper incisor and the ipsilateral canine using a low-speed, straight-handled resin shaping bur and a resin grinding diamond bur.

Post-operatively, depending on the needs, some dogs were given non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or antimicrobial treatment for a few days, while all dogs were given chlorhexidine antiseptic gel (Dentrisept 2 mg/g, Livisto) or medicinal honey cream (L Mesitran Soft 15 gr, Bioskin, Greece). Until the recheck of the animal, it was recommended to feed soft food, avoid chewing hard objects, and clean the orthodontic structures daily to reduce the microbial load of the area and remove food residues.

Results

Fifteen dogs presented to the Clinic with a histo- ry of retained deciduous canines and pain during chewing or occlusion of dental barriers. The age of the animals ranged from 5 months to 3 years (mean 12.3 months), while the body weight ranged from 2 to 78 kg (median 2.6 kg). The majority of dogs belonged to miniature or small breeds such as Pomeranian (the most common breed), Maltese, Pincher, Yorkshire Terrier and Chihuahua. However, a giant breed dog - Central Asian Shepherd - was also presented. The vast majority of animals were female (14/15 animals).

| (1 dog): 1 maxillary deciduous canine tooth | ||

| (4 dogs): 4 deciduous canine teeth |

|

(3 dogs): maxillary deciduous canine teeth |

| (4 dogs): 3/4 deciduous canine teeth | ||

Table 1. Residual deciduous canine teeth.

The main reason for the presentation to the Clinic was the retained deciduous teeth, as they had remained in 12/15 dogs. Of these, in 4/12 all deciduous canines were remaining, 3/12 animals presented with residual maxillary deciduous canines (504, 604), while two of them also had cranial displacement of 104 and 204. In another four animals, three of the deciduous canines remained, of which (in 2: 504, 704, 804), (in 1: 504, 604, 704) and (in 1: 504, 604, 804) while finally, only one canine remained in one dog, 604 (Table 1). The other 3/15 animals presented due to pain and reduced food intake or selective appetite (preferring canned or cooked food instead of dry food). At the same time, 2 of these animals also displayed hypersalivation. Injury to the soft tissues of the area and the presence of ulceration was noted on examination of the oral cavity in two cases, namely in the palatal area near the third incisor and the canine. All animals (15/15) had a lingual displacement of the mandibular canine bilaterally, which was noted on clinical examination.

| (2 dogs): crown extented and elastic orthodontic chain placement - 100% | ||

| (11 dogs): crown extented - 100% |

|

(2 dogs): inclined plane method - 50% - 50% |

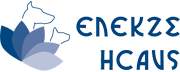

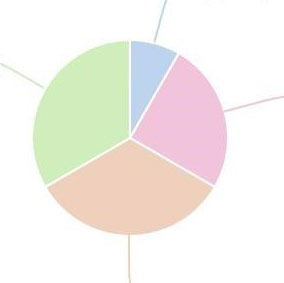

Table 2. Technique method: dogs and success rates.

Two orthodontic techniques were used in the present study (Table 2). In 13/15 cases, the extension of the lower canines was chosen as an orthodontic treatment method. The success rate was 100%, while as an adjunct to the method, an elastic orthodontic chain was applied to hooks in 2 dogs which, due to bilateral cranial displacement of the maxillary canines, showed a reduction in the width of the interdental space between the canine and the upper lateral incisor. The hooks were constructed with metal suture and light-curing synthetic resin, on the canines and the complex of the fourth maxillary premolar and first molar, which were joined together with metal suture and light-curing resin as well. An elastic chain was placed between them to move the upper canines caudally. The method was successful in both cases.

The inclined plane method was applied to the remaining 2 cases, which presented with local soft tissue injury and pain upon occlusion. The success rate was 50%. Undesirable side effects occurred in 100% of this technique, as severe gingival inflammation and mucosa of the hard palate had set in in both animals after the removal of the materials. Fifteen days later, the inflammation had completely subsided after the teeth were extracted and polished, following daily care of the area, with the application of chlorhexidine gel by the owner. The dog in which this technique failed was the only giant-breed dog. The animal was initially fitted with a clinic-made inclined plane, which partially broke after a few days and was repeatedly repaired. Finally, after taking impressions, metal incline planes made by a dental technician were placed, which resulted in severe abrasion and exposure of the pulp of one of the lower canines. In the end, vital pulp treatment was performed, following the reduction of the tooth’s crown length, a method that had been initially suggested to the owner of the animal due to the size of the root of the tooth, but he refused. Due to the large forces exerted during occlusion in the presence of the appliance, joint dysfunction and disruption of occlusion of dental barriers also occurred.

The dogs were re-examined as scheduled one month after the removal of the orthodontic structures and six months later. With the exception of one dog in which orthodontic treatment failed and occlusion remained abnormal, all other animals exhibited normal occlusion and activity.

Discussion

Disruption of the occlusion of the dental arches and, more specifically, of the canines is a fairly common dental-maxillofacial abnormality, which can occur in every breed. Lingual displacement of mandibular permanent canines and cranial displacement of maxillary canines are attributed to genetic predisposition (Furman & Niemiec 2013). Retention of deciduous canines, reduction of the intermaxillary space between the two halves of the mandible, brachygnathism, and unequal development of the two halves of the mandible are the most common causes of lingual displacement of the canines (Kim et al. 2015, Angel 2016, Storli et al. 2018, Peruga et al. 2022). Early diagnosis of the abnormal position of the mandibular canines could be potentially carried out while the animal still has a juvenile dentition but it mainly happens following the eruption of the permanent canines (Caiafa 2019). Owners of miniature and small breed dogs should be informed in time about the retaining of the deciduous teeth and the possibility of malocclusion of the canine teeth, and they, in turn, should train their animals to tolerate regular oral cavity examinations. While all dogs included in the study showed lingual displacement of the lower permanent canines, 9 of them also had retention of the lower deciduous canines. In two of the 15 animals, cranial displacement of the upper canines was also diagnosed. This result is in line with those of other researchers (Bannon & Baker 2008, Peruga et al. 2022), that a frequent cause of this pathological condition is the retention of the deciduous canines or the delay in their extraction, even though the permanent canines have erupted. Discomfort during chewing and during passive movements of the mandible, hypersalivation, and a decrease in the food intake were present in 3/15 dogs, while in the remaining 12, the owners had not noticed any changes in the animal’s behavior. The lingual displacement of the mandibular canines can cause injury to the soft tissues of the area (the gingiva of the maxillary teeth and the mucosa of the hard palate, which can even lead to the creation of an oronasal fistula), damage to the tooth itself (abrasion, fracture, endodontic disease), but also in the teeth of the maxilla, as well as dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint. The above conditions are often painful for the animal during both active and passive mandibular movements (Surgeon 2005, Kim et al. 2015, Storli et al. 2018). In 2/15 dogs, an injury to the mucosa of the hard palate was found on examination of the oral cavity and in one animal an ulcer was also documented in the area of contact of the tip of the tooth’s crown with the mucosa. Secondary pathological conditions such as oronasal fistula, endodontic disease, and tooth attrition were not found in any of the animals included in the study. Probably, the absence of secondary conditions, such as the previous, is related to the young age of the study animals, as the majority of them presented at the age of 5-7 months. At this age, the eruption of the permanent canine is not complete, and the crown of the canine is not at its full length. Therefore, no injury is caused during the movement of the mandible.

In our study, vital pulp treatment was performed in only one case after a reduction of the height of the tooth’s crown. In this dog, an attempt to move the displaced canines to their normal position was made, with the use of an inclined plane made of acrylic material, as well as, at a later stage, the placement of a metal inclined plane. Due to the failure of both of these methods, the vital treatment of the pulp was recommended, as mentioned in the literature (Furman & Niemiec 2013, Legentre & Reiter 2018).

Orthodontic operations aim to restore the normal occlusion of the dental arches, while they do not lead to the loss of any tooth or part of it. In order to attempt such operations, the clinician should take into account many factors, such as the age of the patient, the size of the tooth’s root and the mandible, whether there is sufficient space in the interdental space of the maxillary canine and the lateral incisor, as well as whether the owner can be consistent in what is asked of them and that they understand the significant technical difficulties of these methods in animals. Studies in humans as well as in dogs have shown that following the application of large forces during the orthodontic movement of the teeth or when teeth are moved too quickly, endodontic disease or tooth substance resorptions can occur. For this reason, patients who have undergone orthodontic operations should be monitored clinically as well as radiologically by specialized personnel (Hong et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2015, Villaman-Santacruz et al. 2022). The orthodontic devices remain in the animal for at least 2-6 weeks, depending on the progress of tooth movement.

In our study in 2 cases an inclined plane orthodontic appliance was used on the maxillary teeth. The use of either acrylic or metal inclined planes has been widely known in the veterinary literature for more than thirty years. These structures, which usually include the first or second premolar, the canine and the third and/or second incisor of the maxilla, aim to create an inclined plane, on which the canine of the mandible will impinge and slide towards the normal position during occlusion. With such a construction, the forces exerted during chewing are used to move the mandibular canine to its normal position. Great care should be taken in the way the appliances are placed, as it can interfere with the growth of the maxilla (Surgeon 2005). In addition, a frequent side effect of this method is the significant degree of gingivitis and inflammation of the mucous membrane of the hard palate at the points that come into contact with the acrylic material. This occurs due to the accumulation of microbial plaque and food debris between the soft tissues and the acrylic material. Brushing the structure and, if possible, the removal of microbial plaque and food residues by the owners, as well as the application of antiseptic substances, contribute significantly to the control of inflammation (Pavlica & Cestnik 1995, Surgeon 2005, Bannon & Baker 2008, Furman & Niemec 2013). Inflammation of the gingiva and mucosa of the hard palate occurred in both cases, in which this method was used to treat the lingual displacement of the lower canines. As mentioned earlier, the method failed in one of the two cases, and ultimately, crown amputation and vital pulp therapy were performed. This dog, was the only giant breed dog, and presented to the clinic at the age of 18 months, when the eruption and development of the dentition was complete. The forces exerted on the teeth caused both the destruction of the acrylic material of the device as well as the abrasion and exposure of the canine pulp. The method chosen was not appropriate due to the age, body weight of the animal, and the length of the fully developed root of the tooth. However, as mentioned above, the method was chosen due to the owner’s refusal to be applied the reducing the length of the crown technique, in order to prevent continuous injury of the palatal mucosa, severe pain and dysphagia of the animal.

Mandibular canine crown lengthening with light-curing composite resin is a technique that has been used in veterinary clinical practice for the past twenty years. The size and direction of the lengthening varies according to the needs of each case. In this method, the forces exerted on the teeth during chewing, as well as on the inclined plane, are also utilized. According to Storli et al. (2018), the crown lengthening method has very good results even in teeth that have severe lingual displacement. Due to the nature of the construction and the significantly smaller amount of materials used to expand the crown, there are far fewer unwanted side effects. Also, the normal growth of the mandible is not affected, as the lengthening does not affect the growth lines of the jaw-bones. In addition, if the design, the shaping and the grinding of the lengthening is correct, the soft tissues will not be injured. Great care should be taken when removing the extension, as iatrogenic damage of the tooth stractures or even tooth fracture with or without pulp exposure may occur (Surgeon 2005, Storli et al. 2018, Caiafa 2019). In the present study, there was neither soft tissue or teeth injury during material removal was observed in any of the 13 cases in which this technique was used. However, in 2/13 cases, the extension was detached. In the 1st the extension detached one week after placement, and was repositioned. In the 2nd case, the detachment occurred in the third week after placement. On clinical examination of the second animal, the displacement of the canine was found to be satisfactory and in a normal position and thus it was not repositioned. The success rate of the method in the present study is 100% and is in agreement with the work of Storli et al. 2018, in which it is stated that this method has a very high success rate.

In two of the cases in which mandibular canine crown lengthening was performed, it was deemed necessary to place additional orthodontic brackets and elastic chains to move caudally the maxillary canines. This movement was deemed necessary as the interdental space between the lateral incisors and the maxillary canines was very small, and there was not enough space for the correct occlusion of the lower canines. The use of orthodontic elastic chain to move a tooth can be used either as an exclusive orthodontic technique or in combination with another technique. The tension during its placement is enough to gradually move the tooth, without destroying the periodontal ligament. The chain is placed either in commercial orthodontic brackets or in-house constructions of light-curing synthetic resin and metal suture between the canine and usually two teeth joined with an acrylic material and metal suture (Cai et al. 2015, Kim et al. 2015, Legendre & Stepaniuk 2008). The elastic chain is necessary to be changed every 2-3 weeks, as during this time it loses its elasticity. Any repositioning usually requires at least sedation of the animal and/or general anesthesia. In both animals, the movement was successful in one animal, the elastic chain broke after its second placement, but the interdental space was already sufficient to move the mandibular canine, so the brackets were removed, and the chain was not repositioned.

In conclusion, the appropriate orthodontic technique should be chosen after a thorough examination of the oral cavity and the occlusion of the dental arches, while taking into account the size of the dog, its age and the ability of the owner to follow the necessary instructions for appropriate care of the orthodontic devices. According to the results of the present study, canine crown lengthening led to a successful outcome in all cases, with minimal complications. However, the method was applied only in small or medium-sized dogs aged less than one year, and probably this selection increased the success rate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Corresponding author:

Lorida Olga

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

References

- Angel M (2016) Maxillary Canine Tooth Extraction for Class 2 Malocclusion in a Dog. J Vet Dent 33, 112-116.

- Bannon K, Baker L (2008) Cast metal bilateral telescoping inclined plane for malocclusion in a dog. J Vet Dent 25, 250–258.

- Cai Y, Yang X, He B, Yao J (2015) Finite element method analysis of the periodontal ligament in mandibular canine movement with transparent tooth correction treatment. BMC Oral Health 15, 106.

- Caiafa Α (2019) Base narrow (linguoverted) canine teeth: What is it and how do I treat it? https://mobilepetdentistry.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Base-narrow-linguoverted-canine-teeth.-What-is-it-and-how-do-I-treat-it.pdf.

- Furman R, Niemiec B (2013) Variation in acrylic inclined plane application. J Vet Dent 30, 161–166.

- Hong A, Qing-feng X, Hong-fei L, Zhi-hui M, Ai-qun A, Guo-ping L (2008) Rapid tooth movement through distraction osteogenesis of the periodontal ligament in dogs. Chin Med J 121, 455-462.

- Kim CG, Lee SY, Park HM (2015) Staged orthodontic movement of mesiolinguoversion of the mandibular canine tooth in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 51, 49–55.

- Legendre L, Stepaniuk K (2008) Correction of maxillary canine tooth mesioversion in dogs. J Vet Dent 25, 216–221.

- Legendre LF (1994) Bilateral vital pulpotomies as a treatment of a class 2 malocclusion. Can Vet J 35, 583–585.

- Legendre LF (1994) Treatment of a malocclusion in a dog using both exodontic and orthodontic procedures. Can Vet J 35, 454–456.

- Legendre L, Reiter AM (2018) Management of dental, oral and maxillofacial developmental disorders In: BSAVA manual of Canine and Feline Dentistry and Oral Surgery. Reiter AM, Gracis M ed British Small Animal Veterinary Association. pp. 245-254.

- Luotonen N, Kuntsi-Vaattovaara H, Sarkiala-Kessel E, Junnila JJ, Laitinen-Vapaavuori O, Verstraete FJ (2014) Vital pulp therapy in dogs: 190 cases (2001-2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc 244, 449–459.

- Oakes AB, Beard GB (1992) Lingually displaced mandibular canine teeth: orthodontic treatment alternatives in the dog. J Vet Dent 9, 20–25.

- Pavlica Z, Cestnik V (1995) Management of lingually displaced mandibular canine teeth in five bull terrier dogs. J Vet Dent 12, 127–129.

- Peruga M, Piątkowski G, Kotowicz J, Lis J (2022) Orthodontic Treatment of Dogs during the Developmental Stage: Repositioning of Mandibular Canine Teeth with Intercurrent Mandibular Distoclusion. Vet Sci 9, 392.

- Storli SH, Menzies RA, Reiter AM (2018) Assessment of Temporary Crown Extensions to Correct Linguoverted Mandibular Canine Teeth in 72 Client-Owned Dogs (20122016). J Vet Dent35, 103–113.

- Surgeon TW (2005) Fundamentals of small animal orthodontics. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 35, 869–vi.

- Verhaert L (1999) A removable orthodontic device for the treatment of lingually displaced mandibular canine teeth in young dogs. J Vet Dent 16, 69–75.

- Villaman-Santacruz H, Torres-Rosas R, Acevedo-Mascarúa AE, Argueta-Figueroa L (2022) Root resorption factors associated with orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Med Probl 59, 437–450.