Kyros Chadzimisios1 DVM, MSc, Lysimachos G. Papazoglou1 DVM, PhD, MRCVS, Vasiliki Tsioli2 DVM, PhD, Vasilia Kouti DVM,

PhD, Εleni Basdani3 DVM, PhD, Ourania Farmaki1 DVM, PhD, Dip. ECVD, Tilemahos Anagnostou1 DVM, PhD

1 Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

2 Surgery Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Thessaly, Karditsa, Greece

3 Bessy’s Kleintierklinik, Regensdorf, Switzerland

MeSH keywords:

cat, dog, ear auricle

Abstract

The medical records of 53 dogs and cats with aural haematoma treated with Penrose drainage were retrospectively reviewed. Mean age of the dogs and the cats was 7.6 and 5 years respectively. Otitis externa was diagnosed in 23 dogs and 3 cats and skin disease including atopic dermatitis or pruritic dermatitis, associated with Sarcoptes scabiei, fleas, Malassezia spp. or dermatophytes was diagnosed in 11 dogs and 1 cat. Recurrence of haematoma following Penrose removal was reported in 7 dogs and 1 cat. Those animals were treated with placement of a new Penrose tube. Mild pinna thickening or poor ear carriage was diagnosed in 16 dogs and 2 cats. Cosmetic outcome of the pinna was rated by the owners as good in 26 dogs and 2 cats, as average in 20 dogs and 3 cats and as poor in 3 dogs. No signs of haematoma were reported after a follow-up time of 3.5 years for dogs and 4.5 years for cats.

Introduction

Aural haematomas are blood collections affecting the concave surface of the pinna and are more commonly seen in dogs than in cats (Lanz & Wood 2004, MacPhail 2016). Although the exact cause remains unclear, different mechanisms are implicated, including trauma from head shaking and ear scratching secondary to otitis externa, autoimmune disease, other immunological factors or skin hypersensitivity (Wilson 1983, Dubielzig et al. 1984, Kuwahara 1986, Joyce & Day 1997). However, some animals with aural haematomas show no signs of underlying ear disease. Blood accumulation occurs following separation of the skin of the pinna from the underlying cartilage or within the subperichondral space (Larsen 1968, Dubielzig et al. 1984, Lanz & Wood 2004). If the haematoma is left untreated secondary fibrosis and contraction will result in permanent distortion of the pinna. Treatment objectives of aural haematomas include identification and control of the underlying cause, provision of adequate drainage and elimination of the space between the skin and the cartilage of the pinna (Lanz & Wood 2004). There are various treatment options for aural haematomas, including needle aspiration with local infusion of corticosteroids, tube drainage or incisional drainage. Drainage techniques including teat cannula, Penrose drain combined with corticosteroids or closed-suction drain have been described (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994, Swaim & Bradley 1996, Pavletic 2015). Incisional drainage involves creation of a linear or S-shaped incision with sutures or stents, biopsy punch incisions, or carbon dioxide laser incisions (Henderson & Horne 1993, Dye et al. 2002, Lanz & Wood 2004, Cechner 2014). To the authors’ knowledge, no published studies to evaluate the effectiveness of Penrose drainage alone for the treatment of aural haematoma in dogs and cats appeared in the literature.

The aim of the present study is to retrospectively describe signalment, underlying disease, complications and long term follow-up of 53 dogs and cats with aural haematomas, treated with Penrose drain tubes.

Materials and methods

The medical records of 48 dogs and 5 cats with aural haematoma that were treated in the Companion Animal Clinic of the School of Veterinary Medicine of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, with Penrose drainage, between 1996 and 2016, were reviewed. Data extracted from the records included sex, age, breed, weight, clinical signs and their duration, underlying disease, post-surgical complications and long-term outcome. All animals underwent a complete blood count and serum biochemistry analysis. All surgical procedures were performed by the same surgeon. Each animal was premedicated with dexmedetomidine (Dexdomidor, Orion, Finland) at 150 μg m-2 intramuscularly or acepromazine (Acepromazine, Alfasan, Netherlands) at 0.05 mg kg-1 intramuscularly and butorphanol (Dolorex, MSD Animal Health, New Zealand) at 0.1 mg kg-1 intramuscularly. Anaesthesia was induced with propofol (Propofol, Fresenius Kabi AG, Germany) at 1 mg kg-1 intravenously and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen. Patients under general anaesthesia were placed in lateral recumbency with the affected ear uppermost. An otoscopy was performed for the presence of otitis. A swab for cytology, culture and sensitivity was obtained from the ear canal. The ear canal was flashed with warm saline, dried with suction, scoped with an otoscope, and the appropriate treatment was given. The concave surface of the pinna was prepared for aseptic surgery. A small stab incision was made at both proximal and distal extent of the haematoma right after the aspiration of blood collection with a syringe and needle. The haematoma cavity was flushed with saline, and fibrin and blood clots were removed. A 1/4” Penrose drain tube was inserted through the proximal and exited through the distal incision and the drain was secured in place with two simple interrupted 3/0 nylon sutures at each end. The owner was advised to clean the incisions with swabs dampened with saline twice per day. An Elizabethan collar was placed, and the drain was maintained for 15 days. Tramadol (Tramal, Vianex, Greece) at 2 mg kg-1 per os every 8 hours in dogs and every 12 hours in cats, and meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany) at 0.1 mg kg-1 per os once a day, were given for 5 days. Otitis and dermatitis treatment ware performed concurrently. No corticosteroids were used in this study to treat otitis or dermatitis. Follow-up was performed by re-examination and telephone contact with the owner or referral veterinarian. The owners were also asked to rate the cosmetic outcome of the pinna of their dog or cat as good, average or poor.

Results

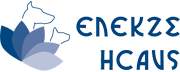

Breeds represented were German shepherd (n=10), French bulldog (n=3), Rottweiler (n=2), English pointer (n=2), Golden retriever (n=2), Poodle (n=2), Bull terrier (n=2) and one of each of Schnauzer, German shorthair pointer, Dalmatian, Cocker spaniel, Collie, Boxer, Great Dane, Canadian white shepherd and Greek shepherd. Sixteen dogs were mixed-bred. Cats represented were Domestic shorthair (n=4) and Persian (n=1) (Figure 1A). Mean age of the dogs was 7.6 years and their mean weight was 28.3 kg. As regards the cats, mean age was 5 years and mean weight was 3.9 kg. Three cats and 31 dogs were male, while 2 cats and 17 dogs were female.

Breeds represented were German shepherd (n=10), French bulldog (n=3), Rottweiler (n=2), English pointer (n=2), Golden retriever (n=2), Poodle (n=2), Bull terrier (n=2) and one of each of Schnauzer, German shorthair pointer, Dalmatian, Cocker spaniel, Collie, Boxer, Great Dane, Canadian white shepherd and Greek shepherd. Sixteen dogs were mixed-bred. Cats represented were Domestic shorthair (n=4) and Persian (n=1) (Figure 1A). Mean age of the dogs was 7.6 years and their mean weight was 28.3 kg. As regards the cats, mean age was 5 years and mean weight was 3.9 kg. Three cats and 31 dogs were male, while 2 cats and 17 dogs were female.

Mean duration of clinical signs was 24.1 days in dogs and 8.8 days in cats. Twenty-eight dogs and 3 cats had the right ear affected and 20 dogs and 2 cats had a left ear haematoma. Otitis externa was diagnosed in 24 dogs and 3 cats. Allergic dermatitis was diagnosed in 11 dogs and 1 cat. Six dogs and 1 cat with otitis had concurrent allergic dermatitis. In 3 dogs the ear was lacerated as a result of a dog bite and 2 dogs also had a benign histiocytoma and a papilloma of the pinna respectively, which were surgically excised. All animals underwent a Penrose tube placement for the treatment of aural haematoma (Figures 1B and 2).

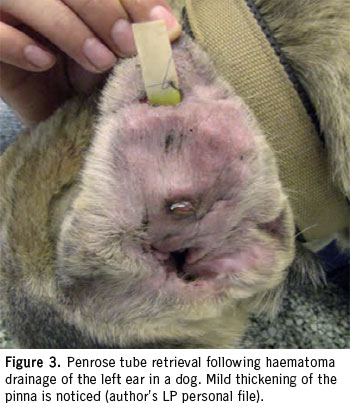

Clinical signs resolved in 41 dogs and 4 cats following removal of the Penrose drain. Seven dogs and 1 cat showed recurrence of the haematoma and 1 dog had an abscess over the medial surface of the pinna. Mean time from Penrose drain removal to recurrence was 5 days. These animals were treated with placement of a new Penrose tube. Out of the 7 dogs who suffered recurrence, 5 were diagnosed with persistent otitis and 2 with otitis externa and allergic skin disease. Mild pinna thickening was seen in 13 dogs and 2 cats (Figure 3). Three dogs showed poor ear carriage. In 1 dog an abscess in the medial pinna was found. The abscess appeared 1 month after removal of the Penrose drain and was treated by lancing and flushing the abscess cavity with normal saline and placement of a Penrose tube to facilitate drainage for 10 days. Clinical signs resolved following tube retrieval. Owners rated the cosmetic outcome of the pinna as good in 26 dogs and 2 cats as average in 20 dogs and 3 cats and as poor in 3 dogs. No signs of haematoma or other ear disease were reported after a follow-up time of 3.5 years in dogs and 4.5 years in cats.

Discussion

Aural haematoma is a disease with no breed or sex predilection (Lanz & Wood 2004, MacPhail 2016). Interestingly, in the present study the majority of dogs affected were mixed-bred and this finding may reflect the dog population in our country. Male animals were also over-represented in our study, reflecting the different temperament and more intense behaviour of males leading to significant ear trauma. The condition was solely unilateral in the present study in contrast to other reports, where bilateral involvement was also reported (Kuwahara 1986, Joyce 1994). In our study, the right ear was affected in more than 50% of the animals, although no location preference was reported by others (Kuwahara 1986, Joyce 1994, Lanz & Wood 2004, MacPhail 2016). Pathogenesis of aural haematoma remains unclear (Lanz & Wood 2004, MacPhail 2016). However, almost 50% of the dogs and most cats of our study had concurrent otitis externa, whereas 22% of the dogs had allergic dermatitis, supporting the view that otitis and allergic dermatitis may play a role in the pathogenesis of aural haematoma. Our findings are favourably compared with the findings of others, where otitis associated with aural haematoma ranged from 36-60% and dermatitis from 18-26% of the 35 dogs with aural haematoma reported (Joyce 1994, Joyce & Day 1997). and are in contrast to the findings of Kuwahara (1986), where 80% of his dogs had concurrent otitis.

Penrose drain placement for the treatment of aural haematomas is one of the most common treatment options as reported in a recent survey among UK veterinarians (Hall et al. 2016). Nevertheless, in the same study, only 4% of the veterinarians selected Penrose drainage as a first option for haematoma treatment, in contrast to 43% that preferred needle drainage combined with local infusion of corticosteroids (Hall et al. 2016). In our study, the Penrose drain tube was easily placed under general anaesthesia, it was well tolerated by the animal and required minimal postoperative management by the owner with no compression bandages placed over the ears. Our findings are in agreement with those of others (Joyce 1994).

In the study presented here, resolution of clinical sings of haematoma was achieved in 83% of the animals. Our results are in agreement with the findings of others, where resolution ranged from 63-85% of the animals treated (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994). However, no actual comparison can be performed between our and the abovementioned studies, since in one study Penrose drain was combined with corticosteroids, while in the other studies different drain tube types were used, including a silicone drain and a teat tube with no consistent drain tube removal times (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994). In the study by Joyce (1994), oral prednisolone was administered to all dogs having Penrose drain placement to help combat otitis externa, allergic dermatitis and postoperative discomfort. No corticosteroids were used in our study, since we evaluated the effect of Penrose drainage alone in aural haematoma management. Interestingly, similar results related to resolution of clinical signs were reported in both our study and the study by Joyce (1994).

Recurrence of the aural haematoma is the most common complication following drain tube removal (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994, Hall et al. 2016). In the study by Wilson (1983), treatment of aural hematoma, using nylon teat tubes, 7 out of 47 cases of canine and feline haematomas recurred. Kagan (1983) treated aural canine haematomas with placement of indwelling silicone drains, where in 2 out of 9 cases, haematoma recurred. In the study by Joyce (1994), auricular canine haematomas were managed with Penrose drains and corticosteroids, and 3 out of 29 aural haematomas showed recurrence. In our study, 15% of the animals showed recurrence of the haematoma, a figure that compares favourably with the findings mentioned above. Persistent underlying disease including otitis or allergic dermatitis might be responsible for recurrence in our study. Early or late removal of the drain tube may also affect the outcome. Duration of drainage lasting less than 2 weeks or exceeding 3 weeks, or inadvertent removal of the drain tube by the animal may contribute to recurrence (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994). However, drainage of chronic haematomas with Penrose tube may be less than desirable, as granuloma formation and fibrosis affect proper drainage (Bellah 2012).

In the present study, we found that drainage of aural haematomas with a mean duration of clinical signs of 16 days resulted in mild thickening of the pinna or poor ear carriage in 34% of the animals. This finding was reflecting the chronicity of the haematoma, or the increased time of drain placement leading to fibrous tract formation and subsequent effect on the cosmetic result (Joyce 1994, Pavletic 2015). In contrast, other authors using drain tubes report no pinna thickening or distortion in their smaller than ours series of haematomas (Wilson 1983, Kagan 1983, Joyce 1994). However, in the study by Joyce (1994), concurrent administration of prednisolone seemed to prevent pinna distortion. Drainage of acute haematomas may have better cosmetic results than drainage of chronic haematoma with long lasting inflammation that results in fibrosis, leading to significant thickening and distortion of the pinna (Pavletic 2015).

In the present study, cosmetic outcome following Penrose drainage of the hematomas was considered good in 53% of the animals, average in 43% and poor in 4% of the animals. Cosmetic outcome was reflecting long term pinna appearance following Penrose removal and might be related to pinna thickening or ear carriage. Our cosmetic outcome was comparable to the findings of others (Hall et al. 2016).

Conclusion

Initial treatment of aural haematoma with Penrose tube drainage was successful in 85% of the cases, with recurrence of haematoma and mild thickening of the pinna being the most common complications. Penrose repositioning resulted in a definitive resolution of the condition. Cosmetic outcome was considered good or average in the majority of cases. Management of aural haematoma with Penrose tube drainage is an effective technique for the management of aural haematoma in dogs and cats.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bellah J (2012) Surgery of the Pinna. In: E. Monnet, ed. Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. Wiley-Blackwell, Iowa, pp. 103–107.

- Cechner P (2014) The pinna. In: M. Bojrab, ed. Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery. 5th ed. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 95–97.

- Dubielzig RR, Wilson JW, Seireg AA (1984) Pathogenesis of canine aural hematomas. J Am Vet Med Assoc 185, 873–875.

- Dye TL, Teague HD, Ostwald DA et al. (2002) Evaluation of a Technique Using the Carbon Dioxide Laser for the Treatment of Aural Hematomas. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 38, 385–390.

- Hall J, Weir S, Ladlow J (2016) Treatment of canine aural haematoma by UK veterinarians. J Small Anim Pract 57, 360–364.

- Henderson R, Horne R (1993) The pinna. In: D. Slatter, ed. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 2nd ed. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 1545–1546.

- Joyce JA (1994) Treatment of canine aural haematoma using an indwelling drain and corticosteroids. J Small Anim Pract 35, 341–344.

- Joyce JA, Day MJ (1997) Immunopathogenesis of canine aural haematoma. J Small Anim Pract 38, 152–158.

- Kagan KG (1983) Treatment of canine aural hematoma with an indwelling drain. J Am Vet Med Assoc 183, 972–974.

- Kuwahara J (1986) Canine and feline aural hematoma: clinical, experimental, and clinicopathologic observations. Am J Vet Res 47, 2300–2308.

- Lanz OI, Wood BC (2004) Surgery of the ear and pinna. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 34, 567–599.

- Larsen S (1968) Intrachondral rupture and hematoma formation in the external ear of dogs. Pathol Vet 5, 442–450.

- MacPhail C (2016) Current Treatment Options for Auricular Hematomas. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 46, 635–641.

- Pavletic MM (2015) Use of laterally placed vacuum drains for management of aural hematomas in five dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 246, 112–117.

- Swaim S, Bradley D (1996) Evaluation of closed-suction drainage for treating auricular hematomas. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 32, 36–43.

- Wilson JW (1983) Treatment of auricular hematoma, using a teat tube. J Am Vet Med Assoc 182, 1081–1083.

Corresponding author:

Lysimachos Papazoglou

e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.