Krystalli A. A. DVM, PhD, Surgery & Obstetrics Unit, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece | Papaefthymiou S. K. DVM, Postgraduate student, Surgery & Obstetrics Unit, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece | Prassinos N. N. DVM, PhD, Professor, Surgery & Obstetrics Unit, Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece | Patsikas M. N. DVM, MD, PhD, Dipl ECVDI, Professor Laboratory of Diagnostic Imaging, School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece

MeSH keywords: coxofemoral luxation, dog, lameness

Abstract

Coxofemoral luxation is a displacement of the femoral head from the acetabulum. Most coxofemoral luxations (75%) are craniodorsal. Ventral and caudal luxations occur less frequently. A 1.5-year-old Greek Hound Dog was presented with right hind limb lameness. Orthopedic examination revealed pain, limited range of motion, and crepitus on passive flexion and extension of the right hip joint. Right gluteal muscle atrophy was also present. Radiographs confirmed the diagnosis of craniodorsal coxofemoral luxation. The owner opted for conservative treatment. Seven years following admission the dog remained free of lameness. Based on the findings of this report not all coxofemoral luxations require surgical treatment.

Introduction

Coxofemoral luxations are common in dogs accounting for up to 90% of all joint luxations (Fry 1974). Causes include vehicular trauma (Bone 1984) severe hip dysplasia, falls, spontaneous occurrence, and unknown causes (Herron 1979).

Most coxofemoral luxations (75%) are craniodorsal (DeCamp et al. 2016), while ventral and caudal luxations occur less frequently (Harari et al. 1984). In craniodorsal luxation, the pull of the gluteal muscles aids in displacing the femoral head craniodorsally to a position adjacent to the iliac body or dorsal to the acetabular rim. The luxation results in tearing of the joint capsule and the round ligament (Wardlaw & McLaughlin 2012) and tearing and contusion of the periarticular muscles and the articular cartilage. Injury in the cartilage also results from subsequent contact and abrasion of the femoral head with the pelvic bone outside the acetabulum, along with loss of lubrication and nourishment normally provided by the synovial fluid (Hulse 2010).

During coxofemoral luxation, one of the changes that could be detected is the development of a pseudoarthrosis with new bone formation on the lateral pelvic side where the femoral head lies. This new bone growth forms a second acetabulum. Additionally, the femoral head and neck can show a variable degree of patchy bone rarefaction and sclerosis. Rarefaction of bone in the acetabular area can occasionally be present. Soft tissue calcifications are often encountered (Stead 1970).

A very rare clinical case of untreated chronic coxofemoral luxation with a favorable outcome is presented.

Description

A 1.5-year-old, male, intact Greek Hound Dog, weighing 22 kg was referred to our clinic for evaluation of right hind limb lameness. The dog was involved in a road traffic accident 5 months ago. Craniodorsal luxation of the right hip joint was diagnosed and conservative treatment (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and controlled activity) had been instituted for 15 days without any clinical improvement by the referring veterinarian. Five months later, the dog was presented to Companion Animal Clinic of Aristotle University Thes- saloniki for further investigation and treatment. Orthopedic examination revealed right hind limb lameness (2/5), gluteal muscle atrophy, pain, crepitus, and limited range of motion during flexion and extension of the right hip joint. Also, the right hind limb was shortened compared to the contralateral. In the ventrodorsal radiographic view, the right acetabulum was shallow, the femoral head was luxated craniodorsally and pseudarthrosis was created. The owner was offered the option of surgical treatment (femoral head and neck ostectomy or total hip replacement), but he opted for conservative management (controlled activity, loss of body weight, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

After 4 months, at the re-examination, lameness in the right hind limb was even slighter (1/5), and gluteal muscle atrophy was also reduced, while crepitus was still intense during flexion and extension of the right hip. Radiographic examination of the pelvis showed right hip luxation, with a craniodorsal displacement of the femoral head which was in contact with the caudolateral aspect of the body of the iliac bone. Mild osteophyte formation in the acetabulum and femoral head and neck was also evident. The left hip joint appeared normal (Figure 1). Due to milder clinical signs, conservative management was continued.

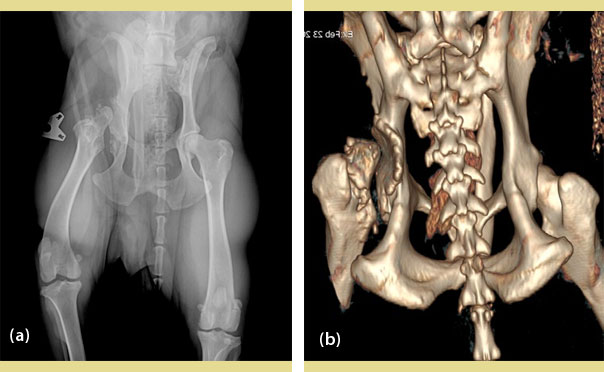

Seven years later at the re-examination, the dog had no lameness, but severe crepitus and restricted extension and rotation of the right hip joint were observed. In radiographic and computed tomographic (CT) examination of the pelvis, the left hip was found normal. Gluteal muscles were shown more atrophic on the right side. The luxated right femoral head was in contact with the caudolateral aspect of the body of the ilium, which appeared obviously concaved surrounding partially the femoral head. There was deformation of the femoral head, neck, and acetabulum due to new bone formation. Tinning of the femoral head with radiolucent areas and osteophytic lesions were observed. Bone loss and bone fragmentation were seen in the femoral head. The right patella was subluxated laterally (Figures 2a and 2b). All clinical examinations were contacted by the same clinician.

Figure 2. Ventrodorsal radiograph (a) and CT (b) of the pelvis 7 years after Figure 1. The luxated right femoral head is in contact with the caudolateral aspect of the body, of the ilium, which is appearing obviously concaved, surrounding partially the femoral head. There is a deformation of the femoral head, neck, and acetabulum due to new bone formation.

Discussion

In the case presented here despite the lesions on the femoral head and the formation of a new acetabulum, the dog remained lameness free in his daily routine and lamed only after intense activity during hunting.

In cats with hip luxation that failed to bear weight on the limb within 4-5 days of the injury, and approximately in all dogs with coxofemoral luxation, reduction, and stabilization of the joint are recommended using closed or open techniques. Joint reduction should be performed soon after the injury to minimize destruction of the cartilage, and before muscle spasticity and fibrosis occur (Wardlaw & McLaughlin 2012). However, conservative treatment can be tolerated in some cats in which, without reduction, a pseudoarthrosis may develop between the luxated femoral head and the caudal portion of the ilium, allowing limited, pain-free function (Ablin & Gambardella 1991). As O’Connor (1938) reported, in the dog, a hip pseudoarthrosis might be so well formed that lameness would be slight. Also, Bruere (1961) reported hip pseudoarthrosis formation as functionally satisfactory in some long-standing cases, complicated cases, and old dogs, except for exercise, when lameness might appear. Our chronic case was in good condition after 4 months and although we gave the option of surgical treatment, the owner elected conservative management because of financial restrictions. Bruere (1961) also found that working dogs with hip pseudoarthrosis were likely to be permanently lame. This was not the case in our report, as our dog had a better outcome. Our dog was followed by clinical examination a subjective method of assessing the gait of the animal. If equipment for gait analysis was available, mild disturbances could be detected. According to the owner, the dog was lame only after intense exercise associated with pseudoarthrosis is an unstable joint.

According to Wolff’s law, the internal architecture and the external form of the bone are related to its function and change when its function changes (Wolff 1986). In our case, a pseudoarthrosis was created so well, that it had an apparently normal gait free of lameness. Possible adequate post-traumatic movement of the limb was the reason for the satisfactory outcome of the dog. Indeed, the pain threshold is different in each animal (Wiese & Yaksh 2015), and it is seen in daily practice in varous painful situations, such as fractures, luxations, etc. It seems that in our dog it was high due to its stoic character. The pain scale that was used, was Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (Hielm-Bjorkman et al. 2009) and the score was five. Under seven there is no chronic pain.

Conclusively, although it is well known that surgical intervention is required for the management of canine coxofemoral luxation, in cases with no treatment, pseudoarthrosis may occur that ensure satisfactory femoral head function and good quality of life, even in working animals. It has been increasingly usual for veterinary surgeons to be asked to discuss the prognosis with non-surgical management of the full spectrum of orthopedic problems, driven primarily by the financial concerns of the owners. Whilst conservative management is not ideal in many cases, including coxofemoral luxation, the key question is whether the patient will have a better quality of life with non-surgical management. The need to redefine nonsurgical trauma management guidelines for owners with financial restrictions and for shelters and rescue groups is required. Defining baseline data for non-surgical management of orthopedic problems in an under-reported population obviously presents ethical and clinical challenges, but these should not be insurmountable (Dyce 2016).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author:

Krystalli A. A.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

References

- Ablin LW, Gambardella PC (1991) Orthopaedics of the feline hip. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 13, 592–598.

- Bone DL, Walker M, Cantwell HD (1984) Traumatic coxofemoral luxation in dogs, results of repair. Vet Surg 13, 263-270.

- Bruere AN (1961) Treatment of coxofemoral dislocations in the dog. New Zealand Vet J 9(4), 70-73.

- DeCamp CE, Johnston SA, Dejardin LM, Schaefer SL (2016) The hip joint. In: Brinker, Piermattei, and Flo’s Handbook of Small Animal orthopedics and Fracture Repair. 5th ed. Elsevier, St. Louis, pp. 468-517.

- Dyce J (2016) Non-surgical management of fractures. In: BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Fracture Repair and Management. Gemmill TJ, Clements DN editors. 2nd ed. BSAVA, Gloucester, pp. 142-148.

- Fry PD (1974) Observations on the surgical treatment of hip dislocation in the dog and cat. J Small Anim Pract 15, 661-670.

- Harari J, Smith CW, Rauch LS (1984) Caudoventral hip luxation in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 185(3), 312-313.

- Hielm-Bjorkman HK, Rita H, Tulamo RM (2009) Psychometric testing of the Helsinki chronic pain index by completion of a questionnaire in Finnish by owners of dogs with chronic signs of pain caused by osteoarthritis. Am J Vet Res 70, 727 – 734.

- Herron MR (1979) Coxofemoral luxation in small animals. J Vet Orthop 1, 30-37.

- Hulse DA (2010) Biomechanics of luxation. In: Mechanisms of disease in small animal surgery. Bojrab MJ, Monnet E editors. 3rd ed. Teton New Media, Jackson, pp. 693-703.

- O’Connor JJ (1938) Affection of tissues: Joints. In: Dollar’s Veterinary Surgery. General, Operative, and Regional. 1st ed. Bailliere, Tindall & Cox, London, pp. 133-146.

- Stead AC (1970) Changes in the hip joint of the dog following traumatic luxation. J Small Anim Pract 11, 591-600.

- Wardlaw JL, McLaughlin R (2012) Coxofemoral luxation. In: Veterinary Surgery - Small Animal. Tobias KM, Johnston SA editors. Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, pp. 816-823.

- Wiese AJ, Yaksh TL (2015) Nociception and Pain Mechanisms. In: Handbook of Veterinary Pain Management. Gaynor JS, Muir III WW editors. 3rd ed. Elsevier Mosby, St. Luis, pp. 10-41.

- Wolff J (1986) Remodeling of the internal architecture and external shape of bones. In: The Law of Bone Remodeling. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 23-74.