Splinaki C. DVM, ΜSc, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Papadopoulou M. DVM, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Chatzimisios K. DVM, MSc, MRCVS, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Angelou V. DVM, MSc, PhD, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Papazoglou L. G. DVM, PhD, MRCVS, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

MeSH keywords: perineal urethrostomy, urethra, dog

Abstract

Five intact male dogs, four mixed-breed and one French Bulldog, with a median age of 5 years underwent perineal urethrostomy for the treatment of traumatic urethral rupture or recurrent urolithiasis. The clinical presentation of the dogs included symptoms of dysuria and urination from the site of the wound or through a urethrocutaneous fistula. The urethrostomy orifice which was 2-2.5 cm long, ended in the perineum approximately midway between the anus and the scrotum. The postoperative complications included hematuria, with a median duration of six days in all animals, while long-term urinary tract infection was observed in one dog. After a median follow-up of three years, one dog died of unrelated causes while the others are in good condition and free of urinary tract symptoms.

Introduction

Urethrostomy is a surgical technique that is applied in case of permanent or recurrent damage to the distal part of the urethra, leading to obstruction of urination. It is performed by creating a new stoma of the urethral mucosa, central to the external urethral orifice, which is sutured to the skin, to permanently divert the normal course of urine (Brown 1975, Smeak 2000, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). During perineal urethrostomy (PU) in male dogs, the urethral stoma, which is 2-2.5 cm long, terminates in the perineal region, approximately midway between the anus and the scrotum (Smeak 2000). It is a surgical procedure most performed in cats and is technically more demanding than other canine urethrostomies, with several potential intraoperative and postoperative complications, both early and long-term, that ultimately limit its application (Brown 1975, Dean et al. 1990, Kyles & Monnet 2013). PU is applied in cases of recurrent obstructive urolithiasis, severe trauma, stenosis, or neoplastic infiltration of the urethra where prescrotal and scrotal urethrostomy are not expected to resolve the problem, are contraindicated, or have failed (Stockman 1972, Brown 1975, Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Davis & Holt 2003). In rare cases, it may be used in animals that need to undergo scrotal urethrostomy but when castration is not desired by the owner or to facilitate easier access and performing surgery to the bladder, prostate gland, and intra-pelvic urethra (Kandel et al. 1992, Taylor & Smeak 2021).

In the international literature there are few reports of clinical cases of PU in male dogs (Stockman 1972, Davis & Holt 2003, Holt 2008), while in female dogs PU is described as part of the surgical resection of the vulva and vagina due to their neoplastic infiltration (Bilbrey et al. 1989). Recently, the surgical technique of PU and its short- and long-term results have been described in 8 healthy male dogs in an experimental setting (Taylor & Smeak 2021). Five clinical cases of male dogs that underwent PU due to injury or obstructive urethral stones were included in the present retrospective study. The aim of the study is to describe the symptoms, diagnostic investigation, surgical technique, and long-term postoperative follow-up of five dogs with urethrostomy.

Description of the cases

The records of five male dogs that underwent surgical repair of urethral patency via PU at the Companion Animal Clinic from 2000 to 2019 were retrospectively studied. Data extracted from the records included sex, breed, age, body weight, history, preoperative laboratory tests (blood tests, biochemical tests, blood gas, urine sensitivity test), and imaging findings (plain abdominal X-ray or even chest X-ray in case of multi-trauma), surgical findings, postoperative complications, and follow up/outcome.

Figure 1. Surgical preparation of the perineum, placement of a «purse-string» suture around the anus.

Figure 2. Separation of the bulbocavernosus muscles.

Figure 3. The urinary catheter can be seen following a midline incision in the cavernous bodies and urethral wall.

Figure 4. Urethra was sutured to the perineal skin.

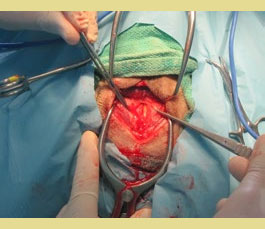

The surgical procedures were all performed by the same surgeon. In the case of post-renal azotemia, metabolic acidosis, or electrolyte disturbances due to obstructive uropathy, preoperative hemodynamic stabilization with fluid and electrolyte administration was performed. For sedation, the animals were intramuscularly administered a combination of midazolam (Dormicum 5mg/ ml, Roche Pharma AG, Germany) at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg and morphine (Morphine Sulfate 10mg/ml, Hameln Pharma, Germany) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg. Anesthesia was established with propofol (Propofol 10mg/ml, Fresenius Kabi AG, Germany) given intravenously in small doses (1mg/kg) until an anesthetic depth satisfactory for intubation was achieved. Anesthesia was maintained with a mixture of isoflurane in oxygen. In addition, epidural infusion of lidocaine mixture (Xylocaine 20mg/ml, AstraZeneca, U.K.) at a dose of 2mg/kg and ropivacaine (Ropivacaine 10mg/ml, Fresenius Kabi AG, Germany) at a dose of 0.4mg/kg was performed for better analgesic effect. Initially, catheterization of the urethra was performed from its external orifice in the penis (one dog) or through the site of the rupture or fistula (four dogs). After the surgical preparation of the perineal region, part of the tail, and the upper part of the hind limbs, the dogs were placed in ventral recumbency with the pelvis slightly elevated and the hind limbs hanging off the surgical table. The tail was elevated and immobilized in a cranial position with the aid of adhesive bandaging tape. A “purse-string” suture was placed around the anus with a 2/0 polyamide suture (Figure 1). The skin incision which was at least 3-5 cm long, was made with a No 10 blade in the midline, approximately midway between the anus and the scrotum. Subcutaneous tissues were then separated with scissors while bleeders were controlled with the help of diathermy. The retractor muscle of the penis was then isolated and pulled laterally using a Gelpi retractor to expose the urethra after the bulbocavernosus muscles had been separated at the midline, and a second Gelpi retractor was placed at this point. Following palpation to locate the urethral catheter, an elongated midline incision of 2-2.5 cm was made in the cavernous body and the urethral wall (Figures 2, 3). Due to the cross section of the corpus cavernosum, significant bleeding was observed, which was controlled by pressure. To secure the urethra to the skin, after removing the urinary catheter, suturing was performed with simple interrupted sutures of monofilament, non-absorbable polyamide 3/0 sutures at approximately 2-3mm from each other (Figure 4). Each suture included 2-3mm of the urethra, part of the underlying cavernous tissue, and 3mm of skin. The remaining skin was also sutured with interrupted sutures, using the same type and size of suture material. Finally, the “purse-string” suture was removed from the anus.

After surgery, a Foley catheter was placed in four dogs through the stoma, connected to a closed urine collection system for the first three to six postoperative days, until edema subsided, and postoperative bleeding was limited. The dogs’ hospitalization in the clinic lasted from two to seven days and they were discharged when it was certain that they were urinating normally through the stoma. In all dogs, an Elizabeth collar was placed until the removal of the sutures, 1014 days postsurgery. During anesthetic induction, cefazolin (Vifazolin, Vianex, Greece) was administered at a dose of 20 mg/kg intravenously and administration was continued at 12-hour intervals. An appropriate antimicrobial drug was administered following a urine culture and sensitivity test. Daily warm compresses and cleaning of the area around the stoma to remove blood clots were performed and water soluble gel was applied every 12 hours at the urethrostomy site (K-Y gel, J&J, USA). Information on the postoperative follow-up and outcome of each case was obtained when the dogs were brought in for re-examination or by telephone contact with the owners or referring veterinarians. Recorded data included the general condition of the dogs, degree of urinary control, recurrence of dysuria symptoms, frequency of urinary tract infections, and the presence of skin lesions around the stoma.

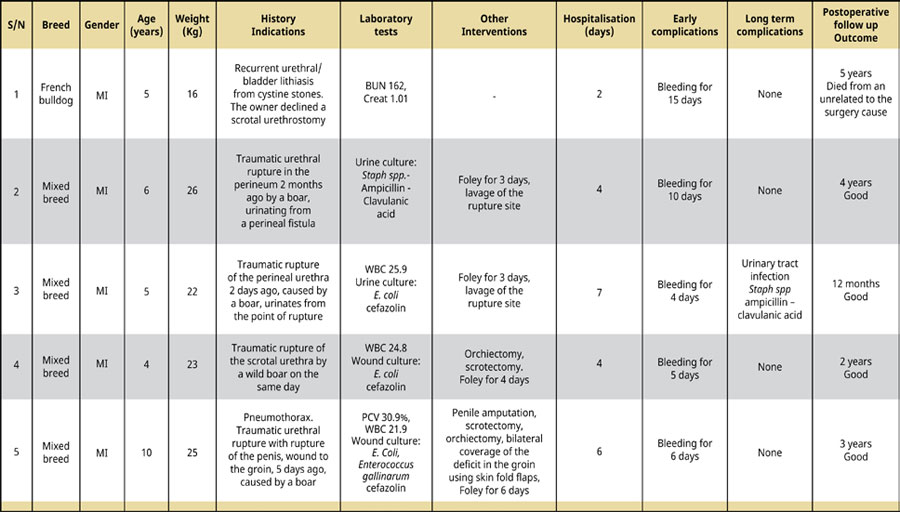

Clinical data are presented in Table 1. All five dogs brought to the Companion Animal Clinic were male and intact. One dog was a French Bulldog and the other four were mixed-breed. The median age of the animals on the day of admission was five years and the median body weight was 23kg.

Table 1. Clinical data of five dogs with perineal urethrostomy.

The reasons for admission included recurrent urethral obstruction by cystine uroliths in one dog whose owner did not opt for orchiectomy, traumatic rupture of the scrotal urethra in one dog, and a urethrocutaneous fistula formation following a traumatic urethral rupture in three dogs. In the latter case, the urethral rupture occurred in the prescrotal area and was accompanied by penile rupture, pneumothorax, and a skin defect in the groin, while in the other two, it was in the perineal region dorsal to the scrotum. In the dog with recurrent urolithiasis, the symptomatology at presentation included signs of dysuria including stranguria and hematuria in the last few days. In addition, the history of this animal indicated that it had undergone a prescrotal urethrotomy 26 months ago, as well as a cystotomy six months ago. In the other animals the urethral rupture had been caused by a fight with a wild boar. One dog was brought in with a scrotal wound on the same day. The remaining dogs were brought in a few days (two dogs) to two months (one dog) after the injury while urinating from the site of the rupture or through a urethrocutaneous fistula (Figures 5, 6).

Figure 5. Urethrocutaneous fistula in the perineum, dorsal to the scrotum.

Figure 6. Catheterization of the urethrocutaneous fistula in the dog of Figure 5.

At the preoperative check-up, the dog with recurrent urolithiasis was found with postrenal azotemia (BUN= 162mg/dL [normal ranges: 10-38mg/ dL], Crea= 1.01mg/dL [normal ranges: 0.7-1.3mg/ dL]). Also, the dog with the prescrotal rupture was anemic (PCV= 30.9% [normal ranges: 37.1-55.0%]). Three of the five dogs showed leukocytosis (WBC: 21.900-25.900/μL [normal ranges: 6.000-17.000/ μL]). In both dogs from which urine samples were taken for culture and sensitivity testing, the results were positive, and Staphylococcus spp. sensitive to ampicillin/clavulanic acid was isolated from the first dog, while Escherichia coli, sensitive to cefazolin was isolated from the second. In addition, Escherichia coli sensitive to cefazolin was isolated from two of the five dogs sampled with a sterile cotton swab from the wound site. However, Enterococcus gallinarum, susceptible to the same antibiotic, was also isolated from the sample of the dog with the rupture in the prescrotal region.

All cases were treated with PU. All animals were catheterized either through the urethral external orifice (one dog) or through the site of rupture or fistula (four dogs). Two dogs underwent both scrotectomy and orchiectomy, and one dog underwent penile amputation, as well as a bilateral skin fold flap over the stifle joint to cover a deficit in the groin. The median hospitalization time for the animals was 4 days. Four dogs had a Foley catheter placed through the stoma postoperatively for three to six days. Antibiotherapy was administered postoperatively to four dogs that were brought in with a traumatic urethral rupture due to a boar fighting. A broad-spectrum antibiotic was administered initially and then according to the sensitivity test result for at least seven days. In two dogs, lavage with normal saline was performed at the site of the rupture during hospitalization. In all animals, frequent postoperative application of water soluble gel to the urethrostomy site was recommended to avoid irritant dermatitis.

The median duration of postoperative follow-up of the dogs was 3 years. Postoperative complications in this study were divided into early, i.e., observed in the first 15 postoperative days, and long term, observed after the first two weeks postsurgery. The most frequent early postoperative complication observed in all dogs was bleeding, both during or regardless of urination, of a median duration of six days, which was treated in all cases with cold compresses or resolved spontaneously. Regarding long term complications, one dog was diagnosed with urinary tract infection three months after surgery, which was treated with oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Synulox 500mg, Pfizer, Italy) for two weeks, following the result of a sensitivity test. Finally, the outcome of the cases was good in four of the five dogs, while one dog died after five years due to unrelated causes.

Discussion

In the present retrospective study, five male dogs underwent PU to restore urine flow interrupted after urethral injury or obstructive urolithiasis. Postoperatively, all animals had bleeding that resolved spontaneously, and one dog developed a urinary tract infection that was treated by administration of the appropriate antibiotic. After a median follow-up of three years, all four dogs were healthy and free of urinary tract symptoms while one died of unrelated causes. In the present study, traumatic urethral ruptures undergoing PU are described for the first time in the literature.

In our study all dogs subjected to PU were male and intact. This may be due to the fact that male dogs, due to their temperament, are more prone to traumatic urethral rupture following fighting with other animals (Selcer 1982, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). They are also more likely to develop obstructive urolithiasis due to the anatomy of the urethra, which is comparatively longer and smaller in diameter than that of females (Brown 1975, Boothe 2000). Four out of five animals in our study were mixed-breed hunting dogs with a traumatic urethral rupture following fighting with wild boars. This finding probably reflects the population of these dogs in our country and the preference for this type of hunting in Northern Greece. The five-year-old French Bulldog was brought in with recurrent obstructive urolithiasis from cystine uroliths. According to a previous study, dogs of this breed have an increased predisposition to obstruction from this type of calculi, especially intact males younger than 7 years of age (Kopecny et al. 2021).

Initial management included stabilizing the dogs’ general condition and ensuring urethral patency. The latter was achieved by catheterization of the urethra, either from the external orifice in one dog, or from the site of rupture or through the fistula in four dogs. In case of urolithiasis, an attempt should be made to direct the calculi to the bladder with the help of saline flushed through the appropriate urinary catheter (Smeak 2000), as was preoperatively done in the dog of our study. Catheterization of the urethra also facilitates its localization intraoperatively and helps to avoid urine irritating dermatitis or to sanitize adjacent tissues in case of traumatic rupture (Stockman 1972, Dean et al. 1990).

Retrograde urethrography is the imaging technique of choice for the diagnosis of urethral rupture (Pechman 1982). However, retrograde urethrography was not considered necessary in the dogs in this study due to our ability to pass the urinary catheter proximally to the site of urethral rupture or obstruction.

Fixation of the urethra to the perineal skin was performed with simple interrupted sutures using a monofilament, non-absorbable polyamide 3-0 suture in all dogs of our study. In contrast to this, in a recent, experimental study of dogs undergoing PU, the use of a synthetic, absorbable glycomer 631 suture was preferred (Taylor & Smeak 2021). The use of an absorbable suture is indicated to avoid urethral injury at the time of suture removal if a nonabsorbable suture is used.

PU is considered to have serious intraoperative and postoperative complications. This is due to the fact that the urethra is located deeper in the perineal region compared to the prescrotal or scrotal area, which makes access more difficult and results in greater tension during suturing and an increased likelihood of dehiscence postoperatively (Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). Moreover, the cavernous tissue around the urethra is thicker at the level of the perineum resulting in greater intraoperative and postoperative bleeding (Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000). Some authors consider that in case of increased tension during the anastomosis of the urethra to the skin, the fibrous and subcutaneous tissue should be initially sutured with simple continuous suture of monofilament absorbable suture to reduce tension (Smeak 2000). This was not deemed necessary in any of the cases in our study. Fixation of the urethra to the skin during PU in the dogs of our study and in the study by Taylor & Smeak (2021), was performed with simple interrupted sutures. In the study of Taylor & Smeak (2021), suture placement was preceded, followed by knot tying. However, during PU in cats as well as in canine urethrostomies, suturing with simple continuous suture seems to have good results as it reduces intraoperative time and postoperative bleeding (Newton & Smeak 1996, Agrodnia et al. 2004). The use of continuous sutures during the anastomosis of the urethra to the skin was not preferred in our study despite the absence of tension. Some authors report that the use of interrupted sutures is for safety reasons (Taylor & Smeak 2021) as continuous sutures could increase the possibility of anastomosis dehiscence.

Four dogs in our study had a Foley catheter placed postoperatively through the stoma, which remained in place for the first 3-6 postoperative days. The necessity of postoperative Foley catheter placement is questionable as it has been associated with urethral narrowing and the occurrence of urinary tract infections. However, it appears to be acceptable in the first 2-4 postoperative days as it promotes effective urinary drainage and accelerates the healing of stoma tissues (Dean et al. 1990, Taylor & Smeak 2021). In our study, keeping the catheter for 6 days in the case of the dog the skin fold flaps was aimed to avoid the complications of wetting them with urine.

Postoperative complications of PU in dogs include bleeding, anastomotic dehiscence, urinary irritant peristomal dermatitis, and ascending urinary tract infection/bacterial cystitis, (Stockman 1972, Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Holt 2008, Kyles & Monnet 2013, Taylor & Smeak 2021). These can be divided into early postoperative, which occur in the first 14 postoperative days, and long term, which occur or continue after this time (Taylor & Smeak 2021). In our study, postoperative follow up of the dogs lasted 1-5 years. The only early complication recorded in all animals was postoperative bleeding lasting 4-15 days during or regardless of urination, which was conservatively treated with cold compresses and an Elizabeth collar until resolution. This appears to be an expected complication of this surgery as it was also seen in 87.5% of dogs operated on in a previous study (Taylor & Smeak 2021). Dehiscence in the urethral anastomosis was not observed in any dog in our study, unlike that of Taylor & Smeak 2021 where 37.5% of dogs showed a small dehiscence that healed by secondary intention.

Regarding long term postoperative complications, one dog in our study developed a urinary tract infection 3 months after surgery, which was treated by administering the antibiotic of choice based on the sensitivity test. In the experimental study by Taylor & Smeak (2021), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was orally given for 1-2 weeks in cases of hematuria or suspected urinary tract infection on macroscopic evaluation of the bladder wall via cystoscopy. In animals undergoing PU, the likelihood of developing ascending urinary tract infection postoperatively is high and should always be managed by sensitivity testing to avoid the development of resistant microbial strains (Brown 1975). Finally, due to the location of PU, postoperative skin irritation due to urinary outflow is a common complication located in the perineum, scrotum, and inner thigh area (Stockman 1972, Dean et al. 1990, Holt 2008, Kyles & Monnet 2013). Irritant dermatitis was not observed in any dog in our study or in any other study (Taylor & Smeak 2021), probably due to the use of the catheter and the application of gel to the area.

In conclusion, PU is applicable in cases of traumatic urethral rupture or recurrent obstructive urolithiasis. PU is an effective surgical technique that can be safely performed in dogs without serious postoperative complications.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author:

Lysimachos G. Papazoglou

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

References

- Agrodnia MD, Hauptman JG, Stanley BJ, Walshaw R (2004) A Simple Continuous Pattern Using Absorbable Suture for Perineal Urethrostomy in the Cat: 18 Cases (20002002). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 40, 479-483.

- Bilbrey SA, Withrow SJ, Klein MK, Bennet RA, Norris AM, Gofton N, DeHoff W (1989) Vulvovaginectomy and perineal urethrostomy for neoplasms of the vulva and vagina. Vet Surg 18, 450-453.

- Boothe HW (2000) Managing traumatic urethral injuries Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 15, 35-39.

- Brown S G (1975) Surgery of the canine urethra, Vet Clin North Am 5, 457-470.

- Cuddy LC, McAlinden AB (2018) Urethra. in Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. jonhston SA. Tobias KM ed. Elsevier, St Louis, pp. 2234-2253.

- Davis GJ, Holt D (2003) Two chondrosarcomas in the urethra of German Shepherd Dog. J Small Anim Pract 44, 169-171.

- Dean PW, Hedlund CS, Lewis DD, Lewis DD, Bojrab MJ (1990) Canine urethrotomy and urethrostomy. Compend Small Anim 12, 1541-1553.

- Holt PE (2008) Urinary tract trauma. in Urological Disorders of the Dog and Cat. Holt PE ed. Manson Publishing, London, pp. 106-122.

- Kandel LB, Harrison LH, McCullough DL, Woodruff RD, Dyer RB (1992) Transurethral laser prostatectomy in the canine model. Lasers Surg Med 12, 33-42.

- Kopecny L, Palm CA, Segev G, Westropp JL (2021) Urolithiasis in dogs: evaluation of trends in urolith composition and risk factors (2006-2018). J Vet Intern Med 35, 14061415.

- Kyles A, Monnet E (2013) Urolithiasis of the lower urinary tract. in Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. Monnet E ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, pp. 528-537.

- Newton JD, Smeak DD (1996) Simple continuous closure of canine scrotal urethrostomy: results in 20 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 32, 531-534.

- Pechman RD (1982) Urinary trauma in dogs and cats: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc18, 33-39.

- Selcer BA (1982) Urinary tract trauma associated with pelvic trauma J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 18, 785-793.

- Smeak DD (2000) Urethrotomy and urethrostomy in the dog Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 15, 25-34.

- Stockman V (1972) Surgery of urolithiasis in the male dog. J Small Anim Pract 13, 635-639.

- Taylor CJ, Smeak DD (2021) Perineal urethrostomy in male dogs-Technique description, short and long-term results. Can Vet J 62, 1315-1322.