Chioti E. DVM, MSc, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Angelou V. DVM, MSc, PhD, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Chatzimisios K. DVM, MSc, PhD, MRCVS, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Papadopoulou P. DVM, PhD, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Papazoglou L.G. DVM, PhD, MRCVS, Companion Animal Clinic, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

MeSH keywords:

dog, prepubic urethrostomy, urethra

Abstract

Seven dogs belonging to different breeds, 6 males and 1 female, with a median age of 4 years, underwent prepubic urethrostomy for the treatment of traumatic rupture, stenosis, or obstruction of the urethra by calculi. The dogs presented with symptoms of stranguria and anuria. The diagnostic investigation included abdominal radiography and retrograde urethrography. The urethrostomy orifice ended laterally to the prepuce in 6 animals and in the midline, in 1 animal. Postoperative complications included hematuria, urinary incontinence, urinary tract infection, peristomal dermatitis, and bladder atony. During a median postoperative follow-up of 4 years, 2 dogs died of other causes while the remaining animals are in very good clinical condition.

Introduction

Urethrostomy is the surgical reallocation of the normal flow of urine through the creation of a permanent stoma by suturing the urethra to the surrounding skin. The main indications for performing the procedure are rupture or secondary narrowing of the urethra after injury or surgery, urethral neoplasms, and recurrent urolithiasis (Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018).

Prepubic urethrostomy (PPU) is a salvage procedure performed in recurrent obstruction or permanent damage or stenosis due to injury of the intrapelvic part of the membranous urethra. It is particularly preferred in cases where other forms of urethrostomy are contraindicated or have failed (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018), as well as in neoplasms of the urinary tract (Brandley 1989). It relies on dissecting the urethra and transferring its orifice to a posterior abdominal position just anterior to the pubic brim (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989). The surgical procedure is not particularly demanding; however, significant potential postoperative complications limit its application in companion animals, particularly cats (Baines et al. 2001). PPU is performed through a midline laparotomy in the posterior abdomen in order to maintain a longer urethra length. The urethral transection is made distal to the prostate in male dogs and near the vagina in female dogs. The urethra is sutured to the skin of the midline incision in female dogs or lateral to the laparotomy in males, through a 450 or less urethrovesical angle (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Dean et al. 1990, Smeak 2000, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). PPU in dogs has not received the needed attention in English-language literature unlike PPU in cats (Baines et al. 2001), as the published number of studies is 2 with a total of 5 cases (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989).

The purpose of this study is to describe the long-term outcome of 7 dogs that underwent PPU. This is the largest clinical study that was carried out in a university hospital and referred to in the international literature.

Materials and methods

For the present retrospective study, the records of dogs that underwent PPU between January 2000 and December 2021, in the Clinic of Companion Animals of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, with a postoperative follow-up of at least 6 months, were searched.

ΑThe following data were recorded and evaluated from the animals’ records: sex, breed, age, cause of admission, symptoms, imaging findings (abdominal radiography and retrograde urethrography in lateral and ventrodorsal views), surgery, postoperative complications, and follow-up/outcome. Follow-up was obtained and recorded after telephone contact with the dog owners or referring veterinarians. The owners or veterinarians were asked about the general condition of the animals, the control of urination, dysuria symptoms, urinary tract infections, and the presence of skin lesions around the urethrostomy.

The surgical procedures were all performed by the same surgeon. Premedication included a2- agonists and opioids. Intravenous cefazolin was administered preoperatively. Anesthesia was inducted with propofol and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen. Animals were given epidural analgesia with a mixture of xylocaine and bupivacaine or morphine. After the initial hemodynamic stabilization with the administration of fluids and electrolytes and under general anesthesia, the dogs were placed in dorsal recumbency and the region from the xiphoid process of the sternum to the pubic bone was prepared for aseptic surgery. This was followed by a midline laparotomy in the posterior abdomen with an incision in the skin lateral to the prepuce in males or a midline incision in the female. The prostate and urethra were identified and the urethra was blindly dissected from the periurethral fat, up to the anterior pubic brim, carefully avoiding trauma to vessels and nerves (branches of the urethral artery and pudendal nerve). After ligation of the distal part of the urethra with a 3/0 polydioxanone suture, the urethra was transected and a suture was placed at the free end of the anterior urethra to allow manipulations. The urethra was brought either through the already existing midline incision (females) or through a small, full-thickness skin incision 2-3 cm lateral to the prepuce (males). The urethra was brought through the abdominal wall muscles, subcutaneous and skin tissues, following a gentle arc to avoid kinking, which would lead to narrowing and obstruction of the normal urine flow. After exiting the abdominal wall, the urethra was spatulated with a 1-2 cm incision, three times the diameter of the urethra, on the ventral surface. The urethral mucosa was sutured to the skin with simple interrupted sutures using a 4-5/0 polyamide or polypropylene suture. Before suturing the urethra to the skin, the laparotomy was closed in three layers as usual. Postoperatively, a Foley catheter in a closed urine collection system was placed, to monitor urination for the next 48 hours. Animals were postoperatively hospitalized in the intensive care unit or in the clinic’s hospitalization room. Postoperative care was the same for all dogs and included: analgesia with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (robenacoxib, meloxicam) and opioids (morphine, fentanyl, tramadol), application of an Elizabeth collar, administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic for 5 days and cleaning of the area around the urethrostomy orifice. In some cases, an antibiotic ointment was placed around the stoma. Urination was then monitored by recording urination frequency and quantity to ensure that the animal was urinating normally.

Results

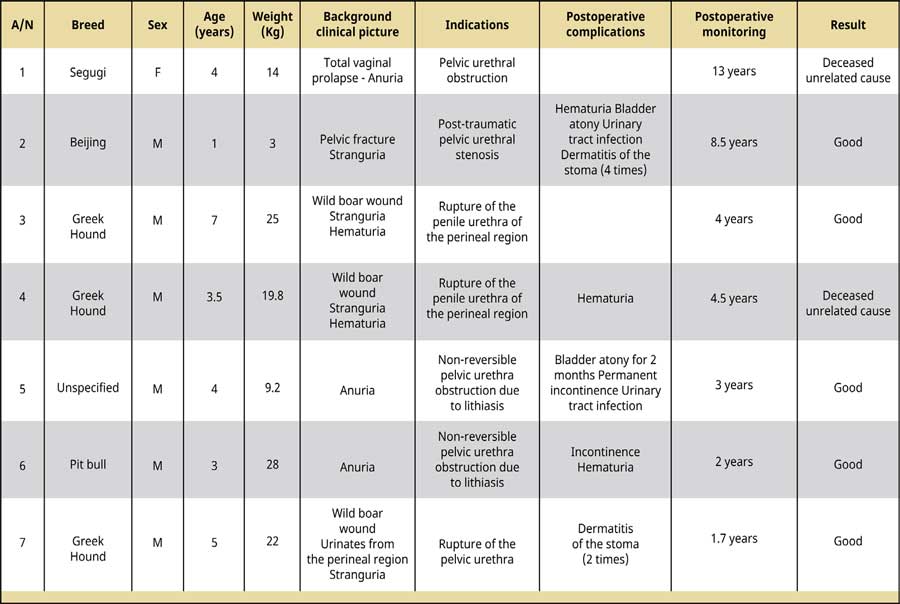

The main clinical data of the study are presented in Table 1. Of the 7 dogs included in the study, 6 dogs were male intact and one was female intact. The breeds represented were Greek Hounds (3 dogs) and one each: mixed breed, Pekingese, American Staffordshire Terrier, and Italian Hound. The median age of the dogs on the day of presentation was 4 years (range: 1-7 years) and the median weight was 19.8 kg (range: 3-28 kgs).

Table 1. Clinical data of 7 dogs that underwent prescrotal urethrostomy.

Indications for surgery were post-traumatic complete rupture of the urethra in 3 dogs (in 1 dog in the intrapelvic portion and in 2 dorsal to the scrotum in the perineal region through rupture of the penis), obstruction of the intrapelvic urethra, at the level of the ischial arch due to calculi and the failure to restore urethral patency by catheterization (in 2 dogs). Other reasons were the inability to find the external urethral orifice due to severe bending and prolapse of type III vaginal mucosal fold in 1 dog, and post-traumatic stenosis of the pelvic urethra due to a pelvic fracture in 1 dog. In the dog with total vaginal prolapse, resection of the prolapsed portion of the vagina through an episiotomy was performed after urethrostomy.

Most cases had similar clinical signs, which included stranguria (4), hematuria (2), and anuria (3), while 1 dog urinated through an urethrocutaneous fistula. The only female dog had a type III vaginal prolapse.

The diagnostic approach included abdominal radiography in all cases, retrograde urethrography (cases 2, 4-7), and ultrasonography in 1 (case 6). Retrograde urethrography demonstrated extravasation of the contrast medium or inability to advance the catheter to the level of the anterior pubic rim due to calculi. Abdominal ultrasonography indicated the presence of calculi in the bladder and pelvic urethra (cases 5, 6). In 2 dogs with rupture of the penis and penile urethra at the level of the perineal region, catheterization of the central part of the urethra was performed and subsequent retrograde urethrography showed no further urethral lesions.

All cases were treated with PPU, following a midline laparotomy, the orifice of the urethra ended 2-3 cm lateral to the prepuce, on the left or right side in male dogs, and in the midline, in female dogs (Figure 1).

Figure1. Prepubic urethrostomy in a female dog with stoma exteriorization in the midline. A Foley catheter was inserted into the urethra through the stoma. The dog’s head is on the left side of the image. (source of the image: Mara Papadopoulou DVM).

Finally, 3 of the 7 dogs that underwent PPU experienced minor hematuria, during and regardless of urination, caused by the exposed urethral mucosa due to its dissection, which resolved within 4 days. Two dogs experienced bladder atony which was treated by Foley catheter placement for 4 days in one dog and lasted 2 months in the other. After removing the catheter, the bladder was emptied mechanically through the abdominal wall for 2 months. Two dogs had a Staphylococcus intermedius urinary tract infection, treated with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for 10 days, based on the sensitivity test, 2 dogs had recurrent peristomal dermatitis (case 2: 4 times and case 7: twice) that was successfully treated by local application of mupirocin ointment for 15 days and 2 were presented with urinary incontinence (cases 5 and 6) which in 1 dog (case 6) was transient and gradually resolved within 7 days from the procedure, while in the other dog, it was permanent.

After a median postoperative follow-up of 4 years (range: 1.7-13 years) [Table 1], 2 dogs died of other causes, while the remaining animals are in good condition.

Discussion

In the present study, 7 dogs underwent PPU due to traumatic rupture, obstruction, or stenosis of the urethra. Postoperative complications were mild and were all managed conservatively. After a median postoperative follow-up of 4 years, 70% of the dogs were alive and in good physical condition, while 2 dogs died of other causes. This is the largest case series in the literature coming from the records of a single university clinic.

Most of the dogs in this study were males. Our results are in agreement with those of other authors (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989). In our study, urethral obstruction due to urolithiasis, and urethral injuries due to wild boar or car accident were seen in 6 male dogs. The increased frequency of urethral injury in male animals may be due to both anatomical reasons (longer urethral length and more superficial anatomical location) and behavioral reasons in males that contribute to being more prone to injuries, leading to urethral rupture. The urethra in female dogs is less prone to injury because it is more flexible, shorter, and not closely attached to bone (Anderson et al. 2006, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). Also, among the intraluminal causes that can lead to a urethral obstruction, calculi are those that are more common in male dogs (Stone & Barsanti 1992). Specifically, the urethra of the male dog follows an abrupt change in its course, at the level of the ischial arch, as it emerges from the floor of the pelvic cavity and is directed anteriorly under the abdominal wall. In addition, at this point, the urethra is surrounded by the ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles. The combination of these factors makes the region of the ischial arch more prone to obstruction by calculi (Stone & Barsanti 1992). In our study, the failure to restore urethral patency was due to the entrapment of calculi and the inability to flush them back into the bladder following catheterization and saline infusion.

The clinical signs presented in the majority of our cases (anuria, hematuria, and stranguria) are consistent with the findings of other authors (Pechman 1982, Selcer 1982, Anson 1987, Cooley et al. 1999).

The imaging examination of choice for the diagnosis of urethral obstruction or rupture is retrograde urethrography (Pechman 1982, Selcer 1982, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). This method was also used in our study to diagnose traumatic pelvic urethral rupture or obstruction of the pelvic urethra by calculi.

Recovery from urethral injury depends on the severity, chronicity, and location of the injury (Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). Three techniques are proposed for the repair of the rupture, including a temporary bypass of the rupture and healing by second intention in cases of partial rupture, end-to-end anastomosis of the urethral ends, or permanent bypass using urethrostomy or tube cystostomy in cases of complete rupture (Pechman 1982, Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Anderson et al. 2006, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). End-to-end urethral anastomosis has a guarded prognosis related to the occurrence of postope- rative stenosis (Layton et al. 1987). Passing a permanent catheter through the anastomosis or tube cystostomy were found not to affect healing and not to cause stenosis (Pechman 1982, Anderson et al. 2006). In the present study, 4 dogs were diagnosed with a post-traumatic rupture of the penile or pelvic urethra, and pelvic urethra stenosis due to fracture. Due to the possibility of postoperative stenosis following anastomosis and long-term morbidity after anastomosis through a permanent catheter, bypassing the rupture by performing a PPU was preferred. The urethra was sutured to the abdominal wall at a gentle arc, in order to prevent kinking and obstruction of the lumen that could result in urinary retention. An enlarged prostate at the time of surgery could also prevent the urethra from being exteriorized. In these cases, a partial prostatectomy is recommended to reduce the tension of the urethral anastomosis to the skin (Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). However, in the present study, a similar technique did not need to be applied even though the male animals were intact but young with no prostatomegaly. In female dogs, the urethrostomy orifice is usually opened in the midline, whereas in males it is opened laterally or within the prepuce. (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Pavletic & O’Bell 2007). In our study, the end of the PPU orifice in the female dog was located in the midline and in male dogs, laterally to the preputial cavity. In our study, it seems that the stoma opening site may not affect the outcome. Postoperative use of a Foley catheter through the stoma for 48 hours is recommended to decompress the bladder and avoid urine at the surgical site (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Stone & Barsanti 1992). In our study, it was necessary to keep the catheter for more days to treat bladder atony in 1 dog.

Postoperative complications of prepubic urethrotomy in both dogs and cats that are reported in the literature include hematuria, urine incontinence, urinary tract infection, stoma narrowing, peristomal dermatitis, and lumen obstruction due to urethral kinking during exteriorization in a sharp angle (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Baines et al. 2001). In the present study, postoperative hematuria, a common complication of all types of urethrostomy, was caused by surgical urethral transection and resolved spontaneously in a short time. Postoperative incontinence can be caused due to shortening of the urethra or damage of the pudendal plexus or urethra during surgery (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Baines et al. 2001). In the pre-sent study, the postoperative incontinence seen in 2 dogs with nonreducible urethral obstruction due to calculi, was attributed to temporary or permanent damage of the pudendal plexus during dissection of the dorsal part of the urethra, resulting in permanent incontinence in 1 dog. PPU causes shortening of the functional urethra and predisposes to ascending urinary tract infection (Dean et al. 1990). In our study, urinary tract infections that occurred in 2 dogs, were treated with the appropriate antimicrobials. It is not known, however, whether the infection preexisted or occurred postoperatively. Peristomal dermatitis and skin necrosis is a common complication of PPU in cats and is less commonly reported in dogs (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989). Urinary incontinence, stranguria after PPU stenosis and fold dermatitis in obese cats are reported as possible causes in companion animals (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Baines et al. 2001). Controlling the possible causes and opening the urethrostomy within the preputial cavity could reduce the possibility of this complication (Brandley 1989). In our study, the local application of antimicrobial ointment in 2 dogs led to the resolution of the problem. Bladder atony is a frequent consequence of long-term distension and injury of the detrusor muscle due to obstruction of the urethra by calculi (Stone & Barsanti 1992). Finally, stenosis is a serious complication of PPU due to a traumatic technique during tissue dissection, inadequate incision on one side of the urethra, increased tension in the area of the urethral anastomosis to the skin, and poor mucosa to skin apposition (Yoshioka & Carb 1982, Brandley 1989, Brandley 1989, Dean et al. 1990, Baines et al. 2001, Cuddy & McAlinden 2018). In our study, none of the dogs had faced postoperative stenosis of the PPU.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, incomplete case file data, the lack of case homogeneity in relation to the indications for surgery, and the small number of dogs that entered the study.

In conclusion, prepubic urethrostomy is a salvage technique in dogs, in order to bypass the lower urinary tract, in case of loss of function due to obstruction or rupture of the urethra. The procedure is performed without difficulty and with no serious postoperative complications.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Anderson RB, Aronson LR, Drobatz KJ, Atilla A (2006) Prognostic factors for successful outcome following urethral rupture in dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 42, 136-146.

-

Anson LW (1987) Urethral trauma and principles of urethral surgery. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 9, 981-988.

-

Baines SJ, Rennie S, White RAS (2001) Prepubic urethrostomy: a long-term study in 16 cats.Vet Surg 30, 107-113.

-

Brandley RL (1989). prepubic urethrostomy. Prob Vet Med 1, 120-127.

-

Cooley AJ, Waldron DR, Smith MM, Saunders GK, Troy GC, Barber DL (1999) The effects of indwelling transurethral catheterization and tube cystostomy on urethral anastomoses in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 35, 341-347.

-

Cuddy LC, McAlinden AB (2018) Urethra. In: S.A. Johnston & K.M. Tobias, eds. Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. 2nd ed. Elsevier, St Louis, pp. 2234-2253.

-

Dean PW, Hedlund CS, Lewis DD, Bojrab MJ (1990) Canine urethrotomy and urethrostomy. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 12, 1541-1554.

-

Layton CE, Ferguson HR, Cook JE, Guffy MM (1987) Intrapelvic urethral anastomosis: a comparison of three techniques. Vet Surg 16, 175-182.

-

Pechman RD (1982) Urinary trauma in dogs and cats: a review J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 18, 33-40.

-

Pavletic MM, O’Bell SA (2007) Subtotal penile amputation and preputial urethrostomy in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 230, 375-377.

-

Selcer BA (1982) Urinary tract trauma associated with pelvic trauma J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 18, 785-793.

-

Smeak DD (2000) Urethrotomy and urethrostomy in the dog Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 15, 25-34.

-

Stone EA, Barsanti JA (1992) Specific Techniques in urologic surgery, In: Stone EA & Barsanti JA eds. Urologic Surgery of the Dog and Cat, Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 116-197.

-

Yoshioka MM, Carb A (1982) Antepubic urethrostomy in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 18, 290-294.

Corresponding author:

Lysimachos G. Papazoglou

e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.